‘Daughters: How to Untangle Yourself from Your Mother’ Do join me - I’ll be delighted to talk to you about the book and why I wrote it and will do a reading at 5pm. You can drop in or let me know in advance. The café is open for tea, coffee, cake and cream teas.

Julia

0 Comments

I recently had the experience of being devastated by someone’s response to request I had made. It wasn’t the content of what they said it was the tone. I had realised my hurt child had been activated and I was distraught. When I reflected, I recognised the pattern. I had reached out for support, which I realised carried a hope that it would bring praise and encouragement. What came back was something I experienced as critical and negatively expressed. This had deep associations for me. I am now in my 70s, so this inner child was hurt a long time ago, and it is a pattern I have become aware of before and, I thought, done some therapeutic work on. And yet, here it was again. I am sure the other person felt they were being helpful; I don’t really think they set out to cause me distress.

This is a similar response to many who carry pain from childhood, and it might not be from the mother, it could be from the father. My book ‘Daughters: How to Untangle Yourself from Your Mother’ focuses on daughters and mothers and I talk about how quickly triggered we can be when an experience in the present is similar to something in the past. What helped move through this?

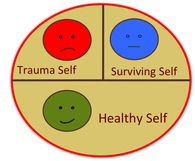

It was a journey (again) through a dark wood. I had also been very tired from having had a lot of work on, so I was vulnerable and didn’t have the resources to protect that hurt child. The important learning is that I came through it; parts of me knew what I needed and helped moved me through while respecting this pain and not trying to push it away. My Healthy Self came back into a leadership position with its ability to calm me, bring curiosity, compassion for myself and creativity. The relationship with our mother leaves all kinds of legacies. This is one of mine. One I had met before several times. It really is a spiral of learning, each time we meet it again we do so from a different point from last time, due to the learning we did then. If it feels familiar to you, maybe map out, like I have done what the stages were and what really helped you to ‘come back’ to the resourceful adult you are. For a while we get stuck in the wounded and hurt child, who may be quite young. I will get to the stage of being able to be grateful to the other person in this instance, for enabling me to learn more about this legacy of trauma. You can order a copy of the book through my website or any book seller. It is available in paperback and e-book. Julia Vaughan Smith Many adult daughters who do things for their mothers end up feeling resentful if they receive no thanks or acknowledgement. It’s not just daughters of course, mothers can feel resentful if their daughters take rather than give in the relationship. Resentment can build up in any relationship. Resentment can eat away at us, fuelling anger and distancing. In this book ‘The Body Says No’ Gabor Maté, a Hungarian-Canadian physician, calls resentment ‘soul suicide’. The problem is in some ways we bring it on ourselves. If we continue to give (time, energy, commitment) in the hope that it will bring recognition and maybe love we are caught in an entanglement. If we choose to give to our mother, or another, then we need to do so freely or not at all. Here’s a made up example – Prue’s mother requires quite a lot of attention from her daughter, not because she is ill or disabled but she wants attention. She is not very focused on her daughter or her daughter’s life. Prue tries to be a ‘good daughter’, to respond to her mother’s requests, to maybe sort out her paperwork, and to ‘think’ for her mother trying to anticipate what might be needed or wanted. Prue has never felt ‘seen’ by her mother and carries this deep hope that one day, if she does enough, her mother will turn to her, see her for herself, and say she loves her. It never happens, so Prue keeps going giving her time and energy, being dutiful, while the resentment builds up and up. She complains a lot about her mother to her friends and hasn’t yet looked at her part in this ‘game’. If she examines her motivation she may find the drivers for this entanglement. Can she bear to break it? Can she bear to set boundaries, to say no, or to limit her contact? Can she bear to break the cycle? She can if she finds it within to honour and respect herself, to step back and look afresh. To decide for herself, what is she willing to do and how does she need to reframe it in order not to feel this toxic build up of resentment. The other thing she has to face is that her mother is highly unlikely to change, if she could be different, she probably would have been by now. She will probably find, in her self-enquiry, that she carries a hope that her mother will change. Best to face the reality that she probably won’t and to plan for that. Good loving relationships comprise equal amounts of give and take, that is, we give to each other and are able to take care and actions that support us from others. Poor relationships are where there is more giving on our behalf than what can be received. We get little support, encouragement or endorsement in return. Sometimes, we are given these things but we block them out, we deny them or they are things we don’t really want and would rather have something else given to us. Healthy relationships can explore that in ways that are not about blame or victimisation, but a clear discussion about what we need. It is useful to remember to create a ‘circuit break’ between stimulus and response. That is between an impulse to react and what we actually do. We can be helped in this by metaphorically stepping back, taking some deep breaths and allowing ourselves to be with the situation. We can engage with the question of ‘what response might I make that will not leave me with resentment?’ This might be linked with an intention not to make the situation worse or to look after our wellbeing by not stepping into toxic resentment. This might give rise to some fresh thinking about what would be the best response, including maybe not responding. In some relationships with mothers, especially when they are ageing and/or vulnerable we may be wish to take on the role of care-giver in some way. We may decide to give our time and energy to making her life as comfortable as possible, without stepping into heroic rescuer, recognising what is in our gift and what isn’t. This needs a deep reality check. We need to make this decision knowingly, weighing up the consequences for us and the potential contributions we can make. We can enrol others to also contribute if they choose. If we can make a clear choice, we have to be prepared to reframe our thoughts so we give the time and energy we have decided to give, without expectation of reward, recognition or thanks. If thanks comes, great, but if it doesn’t we have still given freely of entangled hopes and wishes. In an entanglement it can feel as if we have no choice at all, that the situation is a given as if programmed in from birth. We always have choices and we can take responsibility for the choices we make so that we are not inviting toxic resentment into our lives. Forgiveness can help too, forgiving ourselves for possibly having not done that in the past; we can recognise that our actions came from a place of caring or concern. Engaging our capacity for self- compassion and compassion for our mother may also help. From that position we can engage empathetically with her humanness, and how she may be experiencing that, while not getting caught up in the hurt that maybe her values or opinions are different from ours. It takes work to build up the emotional muscles that enable us to step back, reconsider, decide and act on our decisions, and to let go of the hoped for longing to be seen and feel loved by her. If we are willing to commit to this, it will help free us from the suffering of entanglement. Julia Vaughan Smith March 2023 I first wrote about this in October 2020 after I had completed my research and planning for Daughters: How to Untangle Yourself from Your Mother. What struck me at the time was the guilt some daughters feel talking about their mothers’ failures in mothering; they often qualified what they said with something that excuses the mothers’ behaviour. More recently, this ‘commandment’, Thou Shalt Not Betray Thy Mother, appeared again, this time within me. As I get near to publishing the book I can be overtaken by anxiety that I am betraying my mother for even suggesting that our relationship was difficult at times for me. One of my motivations for writing the book was to give voice to all the daughters who have suffered to a greater or lesser degree from the way their mother related to them, from conception onwards. Many things affect how mothers relate to their daughters, including their own psychology and childhood experience, the circumstances at the time of pregnancy and afterwards, the support around them, life circumstances, as well as the behaviour of the infant and how well that could be tolerated. A number of daughters have suffered greatly from abusive, neglectful, critical or narcissistic mothers, and have largely kept silent outside, perhaps of a therapy room. Some mothers weren’t able to protect their daughters from physical or sexual abuse, and some refused to believe stories of sexual abuse so daughters kept quiet out of fear of not being believed – and in some cases to protect their mother and the family. It's not that there is nothing to say. It’s that the commandment endorsed by society keeps daughters silent. Within this I think there are a at least four reasons some of which I referred to in the blog of October 2020:-

Throughout this book I have been determined not to blame mothers; and indeed, see blaming as part of the unhealthy entanglement. Mothers are daughters, with their own childhood history and stresses in adult life. There are few places where mothers can talk about any negative mothering experiences for fear of being shamed. Some act out of their stress and emotional trauma in their behaviour towards their children. The response of our neuro-physiology in responding to a sense of danger doesn’t concern itself with the motivation of the mother’s action. Many mothers have a motivation to ‘be a good mother’, I doubt any set out to fail their daughters (or sons). However, if through their own psychological development they are unable to feel a strong loving connection with their child their behaviour may at time have been rejecting, hurtful and frightening. A pattern of leaving an infant hungry for too long, or crying alone for too long, produces a fear response in the infant and a lack of trust in the carer. Each generation has its own ‘mothering/parenting guru’ or instructions/expectations. Mothers who want to be good mothers, and who don’t trust themselves to do that naturally, may take on those instructions even where they may not really be in the best interests of the child. In my childhood, it was 4 hour feeding, whether the infant was hungry or not, and no matter how much the infant might have been crying due to hunger. Fashions have changed but the challenge for mothers continues. Is it possible to bring understanding and compassion for mothers and be able to talk of our own experience without feeling we are betraying them? I’d like to encourage us to try. It may be in how we talk about the relationship, and the extent to which we are owning our own part of it as an adult. There may also be some things that we should be mindful of sharing widely out of respect rather than because we feel we mustn’t. We may need to examine the narratives we use more deeply as it is easy to get into a story pattern which leaves out some elements. At the same time, we need to feel able to talk about our own experience and the impact on us, without feeling we are betraying another. Protecting those that hurt us makes sense when we are children, as we have nowhere else to go, but as adults we can come to this with a different mindset. Julia Vaughan Smith March 2023 Three things motivated me to write this book; firstly, the 15 years I spent learning about emotional (attachment or developmental) trauma; secondly, my interest in the Death Mother archetype talked about by Marian Woodman and latterly by Daniela Sieff. Finally, wrapped around both was, of course, my own relationship with my mother that I wanted to explore more deeply. Through developing a deeper understanding of emotional trauma I became curious about a mother’s response to her daughter left its mark from conception onwards. Up until then I had had some understanding about the impact of physical and sexual abuse on children and noticed that adults who showed signs of emotional trauma had not necessarily been subject to such abuse or neglect. One suggestion made on me was that this was a result of many women failing in their attempt to end their pregnancies. I wasn’t convinced by this; while recognising that for many women being pregnant is not what they want, or the circumstances they find themselves in are far from ideal for becoming a mother. This led me to read about maternal ambivalence, the potential swing between love and hatred for the infant, and how, while this is not a rare experience, it is one that mustn’t be talked about. Some writers say that it is the shame of experiencing this that is devastating to the mother, and that talking about it would feel unbearable. It is also likely that the woman would be criticised or seen as a bad mother, which she isn’t. Thus women suffer in silence. Putting this together with my understanding of the neuro-physiological response to threat and feeling unsafe, it seemed to me that infants would sense any hint of hatred in the mother and their trauma response would be activated. The more frequent this was, or the extent to which it was enacted, would deepen the trauma wound. The evidence suggests that mothers who are well supported in pregnancy and afterwards, and for whom the pregnancy is welcome, are better able to manage any maternal ambivalence. Those in different circumstances may find that more challenging. About the same time as I was researching this, I had come across the Death Mother archetype described by Marian Woodman, a Jungian psychoanalyst. I am not a Jungian trained therapist, so my interpretation may not be absolutely correct, however, my understanding is that archetypes are active within our psyche and have a strong influence on our behaviour. The All Loving Mother is another such archetype, the Death Mother being the shadow side. The Death Mother wants to kill off the person they have ‘entered’, not literally, but kill off their creativity and life energy. This appears as a voice or thoughts about ourself for example, ‘I will never be any good’; ‘this project will fail’; ‘this book is a waste of time’ and ‘I am useless’. I have experienced what I call ‘Death Mother’ psychic attacks on my creativity, my work and on my value. They are like being rolled over, in a storm of anxiety and terror. I had one a few weeks ago when about to press the button to publish this book. I became terrified that I had betrayed my mother (and there is a widely held belief that ‘thou shalt not betray thy mother’) and mothers in general. I convinced myself in that state that I should not publish the book. It lasted a few days and was distressing. I brought myself out of it, by chance, thinking ‘well if I don’t publish it, it was cheaper to write it than to have had 3 years of psychotherapy’ and that made me laugh! I came back on stable ground. I know I have written compassionately about my mother and mothers throughout the book. I had set out determined not to vilify, label or blame mothers as I saw that as part of the problem. How does this archetype get into us? It could get into us from our actual mothering, perhaps our mother’s maternal ambivalence or cruelty created this internalised version within. It could be from other carers, a grandmother or teachers. When reflecting on it myself, I recognised that my teachers in the later years of junior school were focused on diminishing us, not celebrating us, we ‘had to learn our place’. This of course reflected the patriarchal society at the time (and is still around of course just differently expressed), containing the embedded messages about women’s place and against creativity and individuality. These have affected our female ancestors back in time, as have other embedded messages for example about race or within some religion. Key to much of this is shame, and what Daniela Sieff refers to as ‘toxic shame’ that is associated with aspects of mothering. A mother who feels shame finds it hard to relate fully to her daughter (or son), she may believe she is a bad mother or she may blame the baby – in either case pushing them away. The idea of a ‘mother entity’ who wants to do us harm is a challenging idea for many. The prevailing myth is that mothers are all loving. I know from my experience as a psychotherapist and friend this is not true. I interviewed a number of women researching the book and what became clear was the depth of pain and suffering around in relation to adult daughter relationships with their mothers. That shifted my focus, from the Death Mother, to that of daughter:mother relationships, as I wanted to write something that would be of value to those who wanted to understand more and change their part of these relationships. I recognised that daughters entangled in these ways with their mothers felt they had no choice, feeling caught like flies in a spider’s web. I also wanted to use the process of writing to enquire into my own relationship with my mother. My first working title for the book was ‘On Being a Daughter’ as I wanted to explore that more deeply for myself. I learnt so much as I did my reflective writing in parallel to writing the book content. I realised how I had become locked into a narrative that left me as the hurt one, and how I used the narrative to repeatedly hurt myself without taking a wider perspective. I realised what my part of the relationship was as an adult. This brought me up short many times. I also stayed with what I knew of my mother’s childhood experience and found a place of embodied compassion for her which honestly wasn’t really there at the beginning. It struck me how we were both deeply affected by the loss and unprocessed grief in our lives and how that contributed significantly to the relationship we had. As I said earlier, it was therapy by writing and exploration, and through facing some truths about myself. The book has ended up as a self-coaching book for daughters and will also be useful to coaches and counsellors in respect of their clients. I hesitated to write a self-help book, and like how one Agent described it ‘this is an intelligent book for an enquiring reader’. While the focus is on self-enquiry and changing our patterns from ‘there and then’ operating in ‘the here and now’, I wanted to have some theory about childhood influences and emotional trauma. I talk about some of the challenges about finding compassion for mothers who have been cruel or abusive, and that we need to have compassion for ourselves first. Personal change is able honouring and resourcing ourselves, facing our truth, and self-enquiry without judgement. We need to become our own loving mothers more of the time, so we do not entangle others in the hope they will become that for us. We need to give up on the wishful thinking that ‘if only we do enough, or find the right way in, our mother will become who we desire’. I end with a quote from Marion Woodman, which I can’t find the source for, but will be from one of the books listed below: “ One half of the wound of life comes from the direction of the father and the masculine energies. The other half of life’s necessary wound comes from the mother world and the place of the feminine energies. Where the blow of the father may feel like a curse to be overcome, the wounds from the mother have the feeling of a spell that binds the soul.” You can buy Daughters: How to Untangle Yourself From Your Mother from online book sellers, some book stores or directly through my website HERE

©Julia Vaughan Smith March 2023 Sieff, Daniela (2009) Confronting the Death Mother:An Interview with Marion Woodman The Psychology of Violence Journal of Archetype and Culture Spring 2009 Sieff Daniella (2017) Trauma Worlds and the Wisdom of Marion Woodman Psychological Perspectives 60:2, 170-185 Woodman Marion (1980) The Owl was the Bakers Daughter. Inner City Books Woodman Marion (1985) The Pregnant Virgin. Inner City Books Woodman Marion (1982) Addiction to Perfection. Inner City Books Parker Rozsika ( 1995) The Experience of Maternal Ambivalence: Torn in Two. Virago Press I have been rereading Joan Halifax’s book ‘Standing at the Edge’. In it she explores what she calls ‘edge states’ within six virtues (altruism, respect, empathy, integrity, engagement and compassion). She looks at the positive and negative expressions of them; the edge is the point where tipping into the negative is possible.

In her section on ‘engagement’ she talks of burnout, which she puts under the heading of ‘falling over the edge’. While having known about burnout for many years, I realised, with shame, that I had never looked into who identified and named it. From Halifax I learnt that it was Herbert Freudenberger, a mentee of Maslow (of hierarchy of needs fame). Freudenberger had been born into a Jewish family seven years before Hitler and the National Socialists came to power and, following his family having all their assets taken, was able to get to the USA on his own, aged 12. He was neglected by his step-aunt and had to find ways to survive on his own, including living on the streets. He was, apparently, a ‘....driven man who worked 14 – 15 hour days until he died’. Halifax quotes his son “His early years, unfortunately, never left him. He was a complicated man and deeply conflicted because of his upbringing. He was a survivor” Those who are trauma-aware, will recognise signs of trauma. How wonderful though that this deeply conflicted and driven man brought understanding to the world about a condition that is widespread. I fear it is possible that Covid-19 may see more cases of burnout in those who are in people-facing occupations, dealing with low staff numbers and increased pressure, while wanting to bring compassion and care to those served. Freudenberger described burnout as being, I quote from Halifax, “…a state of mental and physical exhaustion caused by one’s professional life” and “…the extinction of motivation and incentive, especially where one’s devotion to a cause or relationship fails to produce the desired results .” Beneath the potential for getting burnout are our own issues concerning ourselves. These might arise from our own trauma and be linked with wanting to feel valued, wanting to rescue (what Halifax terms pathological altruism), an identification with our profession and an inability to create and maintain healthy boundaries. Where this is the case, there are always occupational areas willing to drive these people hard and expose them to enhanced stress. I read today that some NHS staff are working 36 hour shifts; they do so from their commitment to their patients and their profession and the system demands it of them. Halifax reminds us that it can be beneficial for some workplaces to burn us out as a way of subduing us; while rewarding us for ‘drinking the very poison of work stress’. Emotive words but I welcomed her stating the reality. Halifax, again talking of Freudenberger’s work with his colleague Gail North, describes the story line they described that leads to burnout:

With the inefficiency that inevitably travels with emerging burnout, we feel we are failing at what we set out to achieve and that is a step away from the work coming to seem meaningless. The issue, using survival language, is our entanglement with it. Maybe we need to be super-aware of the potential for burnout in some of our clients, especially those who are in the NHS, education and social care. I recognise that, as burnout is so common, many of you will be very familiar with its signs and maybe with its treatment. I remember a coaching demonstration at a UK Conference many years ago, where a very well respected coach was coaching someone with burnout. Many of those watching, said it was therapy and not coaching. The coach was robust in his view that he was coaching; I think the exchange was an example of how sometimes coaching pushes things away as being about ‘therapy’ rather than engaging with what the coaching contribution is to this client’s situation. Sometimes, of course, coaching may not the be best intervention, or we the coach might not be the best person, but that is something for us in supervision. Joan Halifax writes from the Buddhist perspective, a compassionate and inclusive approach. While there are a few elements that I take a different perspective on, I recommend her book for understanding these key virtues and navigating our way to ensure we don’t trip into the negative expression (her term) or into survival strategies (mine). The negative is harmful to us and to those we seek to help. Julia Vaughan Smith November 2020 Halifax J (2018) Standing at the Edge : Finding Freedom where Fear and Courage Meet. Flatiron Books, NY In my interviews and through my writing this injunction is often not far away. Talking about experience that was not good for us as a daughter often comes with some sense of guilt and a desire to say ‘but she was under great pressure’ even when the behaviour of the mother is harmful.

I think this is for two reasons. Firstly, most of us recognise that being a mother is not easy for many, from the very beginning and through to the daughter being adult. There are huge societal pressures and expectations placed on mothers, telling them what they must, mustn’t, or have to do ‘for the baby’. Each generation has its own set of demands on how mothers are expected to present themselves to the world. If they fail to comply with these rules, then watch out for the attacks on them. Their autonomy as a mother is regularly undermined, including at times during childbirth. We recognise the gendered issues for all women, and those particularly focused on mothers. At one level, we protect her as we know women are so often not protected. At the same time there is a societal illusion of the all loving and giving mother. The reality is often very far from that for the mother, as well as the daughter. The second reason, therefore, is because we too, are supposed to uphold that illusion; we take in an unspoken requirement that we should protect our mothers from being exposed as falling short of that impossible ideal. To break the silence is to be exposed. Before all the mothers rush to protest, this is not about blaming anyone. Mothers are also daughters, they carry their own daughter experience within them as a mother. That might have been a damaging relationship for them. They are put under incredible pressure, and there are few places where mothers can talk about the stresses for them without feeling shamed. Writers about the common and understandable experience of maternal ambivalence, the swing between love and hate towards a baby, say the problem is how shamed mothers feel about it. That means they don’t talk about it with others or get support for themselves in the day to day care for their child. Those who have a lot of support around them are held in these pressures; those who don’t are more vulnerable to them. The response of our neuro-physiology to a sense of danger doesn’t concern itself with the motivation of the mother’s action. It responds to subtle or not so subtle indicators of being unsafe. For example, in my infancy the ‘feeding rule’ was to feed 4 hourly regardless of infant hunger, or of maternal discomfort. It was about training and giving the mother time for other things (usually domestic). My mother followed that wanting to do the ‘right thing’ for her daughter. The impact on me must have been that at times I was left very hungry for a time or fed when I wasn’t hungry; I had no autonomy or say in the matter. Every time this happens it leaves a marker of lack of safety and mistrust. If repeated often, those markers become deeper and ready to be enhanced by any further action which produces a similar response. The motivation was to ‘be a good mother’ but the impact doesn’t take that into any consideration. There are all kinds of stories I have heard when the mother might say ‘I did it for your own good’, but that can include being hit, restrained, put in a cupboard ‘until you can behave’. These are not good for us and we become silenced by the need to keep the illusion alive, because talking of these things can be shameful and we are often told we are over-sensitive or making it up. Some mothers are cruel to their daughters, are negative and controlling, or undermining and smothering, or addicts or make unreasonable demands on a young child. I am afraid that is the truth. I am writing about this to bring compassion for mothers in terms of their own daughter experiences and the pressures and demands on them; and to help daughters talk about their truth and how that affects them now they are adults. As adults we have resources available to us that we didn’t have as children and we can become aware of, and change, how we continue to respond to our mothers, externally and internally, and step out of an entangled relationship with her. Julia Vaughan Smith October 2020 Next blog in November: The Death Mother It is the issues and circumstance of the coaching which have been changed by the pandemic, but not the principles and process of coaching. They remain the same. We, as coaches, are of course affected, too, and may bring that into our coaching. We need to be sure that what we bring is valuable to the process and not our survival parts. These are just a few of the issues to reflect on: Habits The pandemic, and the lock-down, have broken many of our habits, our established ways of structuring and organising our engagement with the world. We are being required to establish new habits. At the same time, it gives us an opportunity to think which of our habits do we want to let go, following this phase and which new ones might we want to put in place? For example, with developing skill in using online platforms for meetings, could that continue for parts of our work? For coaches, it can widen our client base nationally and internationally. Many coaches already work in that way and have skills and learning they can pass on. For clients, it may lead to a rethink of how they want to organise their work. Some clients may welcome the requirement to be at home, even to stop work (for those furloughed), and enjoy the absence of the daily travel and the other work-related habits. This may bring about some enquiry about ‘what would I rather have from now on, if I could have it?’. There will be those who face a major change in their work habits. For example, if their business or the focus of their work is changed forever by the pandemic. I am thinking of small businesses, the retail and hospitality industry and the tourism industry. However, coaching has approaches for supporting clients in this situation. It may be more intensive than pre-pandemic but we can help the client hold their vulnerability and self-regulate so that they can think their way through their situation. Performance expectations It is unrealistic to think that most of us can achieve the same level of ‘performance’, that is work outcomes, at this time. There will be exceptions of course and some may find that the opportunities for entrepreneurialism are liberating and their outcome is enhanced. For others though, they are learning how to use online platforms effectively, how to stay connected in meaningful ways with work colleagues, how to juggle the boundaries and demands of being a home-worker. This learning takes time. Working online can take away our boundaries, between home and work, and who has access to us, andwhen. It helps to be aware of how these boundaries have been broken down by the pandemic and what ones need to be put in place as part of this new learning. Thought habits It is also an opportunity to notice and reflect on our thought habits; those thoughts that emerge in response to the situation and what is required of us. They could be thoughts about danger and lack of safety, or about our self-worth or our isolation. These are usually negative thoughts that leave us feeling worse than we would if we could think something differently. We all have thought habits, we hear them as our clients talk and we hear them in our own heads. We can capture these and write them down and identify what feelings they generate and what behaviour that leads to. We can change our thoughts without escaping into positive illusion. “What could I think instead, which would still be authentic?”. I am using the term authentic to refer to that sense that it connects with our inner experience. Isolation impacts on us all, for some more than other. Especially affected are likely to include those where isolation is a feature of their earliest experience for example, hospitalisation as a child or being passed through the fostering system, or with parents who were unable to connect with us. This experience in the ‘there and then’ and can be recreated in the ‘here and now’ if we tell ourselves how isolated we are. The question is ‘how am I isolating myself, now?’. We can become identified with those who isolated us and with the experience of being isolated, that we fail to take healthy action for ourselves in the present. Similarly, if we feel uncared for in the present, we may well be identifying with the past. The question is ‘how am I failing to care for myself now?’ or ‘how can I feel my own love and care for myself?’. Many of us will have to practise these kinds of enquiries as our identification is a survival strategy from ‘there and then’ and has become such a thought habit that we often don’t even notice it. Like all habits, we only notice them when they are taken away or when we set out to pay attention. The stories we repeat about our past are also thought habits, we use them to reinforce our feelings of not being wanted, loved or protected in a way that we feel is in our control. Those feelings are there, the pain of them remains in the trauma self, but ironically using our stories to keep us imprisoned in the ‘here and now’ blocks our ability to connect with and process the pain. This became clear to me, personally, last week when I was reflecting on some writing I was doing on mothers and daughters and thinking about memoir writing. Was I using the story to ‘justify’ my thought habits and avoid looking into myself for my own capacity for self-love? We can support our clients to see their thought habits and decide how useful or avoidant they are to them right now. Fear and anxiety It is understandable that there are heightened feelings of fear and anxiety at this time. Those whose core position is not to feel safe, due to their history, are likely to feel these acutely. Often, behind these feelings will be thought habits fuelling them too, that is bringing the past into the present which is not as dangerous as the response implies. We can explore these in ourselves and with our clients. We can help our clients develop processes that support their self-regulation. If we are in a state of fear or anxiety, we cannot find a place of safety, we become frozen. If we are sufficiently free of these emotions with our clients, we can act as a co-regulator with them. We can listen, be with their vulnerability, and support them in accessing other parts of themselves which aren’t overwhelmed by these feelings. Remember, working with parts is a very valuable process (see October 2019 blog). Guilt I feel in a bit of a bubble here in East Devon where the virus numbers are low, and I have a sunny garden and the sea is a 5 minute walk down the lane. I was part of an online group discussion on Saturday, and heard again (having heard it several times from friends) ‘I feel guilty that I am quite enjoying the lock-down and can get out, when so many can’t’. I have also had conversations with friends about ‘I feel I should be making a contribution by doing something’. The important thing to hold onto is that it isn’t either/or. We can feel privileged in our situation AND feel compassion for those that are in vastly different situations. We can decide if we want to take any action, and if so, what; and it is okay if we do or we don’t. The ‘shoulds’ are the clue to these being the equivalent of ‘parental injunctions’. We can also use this pandemic to become more aware, if we chose to, of the divisions and differences in the society we have helped create. Guilt is only useful if it triggers some thing we need to learn about how our action has transgressed our value system; for example, if we have stolen something or spoken harshly. Feel it, note it, move on. Often though it is a seeping ‘sore’. A friend sent me this in an email exchange about guilt: ‘and guilt, like the autumn leaves, has served whatever purpose it ever had and now withers, flutters and becomes useful as compost. ‘ We need to be sure that what ever action we take comes from our healthy self and that it isn’t a ‘reaction’ from our survival self needs for validation or rescuing. In terms of what to say to those who talk of their different situations, if we are truly listening from our health self resources, we will be connecting with the client and the words will come. If we are in our survival self we won’t have that connection and we may well say something that doesn’t land well. If we can stay in our healthy self-regulated state a lot of the time, we can be with our clients in whatever situation they come to us in. We don’t need new tools and techniques. We just need to listen fully, be present and use our coaching expertise effectively. Julia Vaughan Smith | April 2020 Author: ‘Coaching and Trauma: From surviving to thriving’ www.juliavaughansmith.co.uk www.coachingandtrauma.com #coachingandtrauma #traumainformedcoaching Since the social isolation started three weeks ago, I have observed my own survival parts activating as my autonomy and freedom is limited and I am physically isolated from those I love and care about. For many of us this stimulates our early trauma emotions which switches quickly to survival behaviour. I noticed this morning a sadness from grief: I could feel that sadness and loss, but I was also aware of a potential shift into survival self-pity. Could I just allow the sadness to come and then go?

We will all have seen our own survival responses and those in the communities we are part of. Our rush to judgement, maybe, at those not ‘abiding by the rules’; being bad tempered and easily offended; being in ‘survival manager’, a form of control; denial; numbness, drinking more; or falling into a ‘victim attitude’. Some people might have become addicted to social media or the news in an attempt to manage their fear, when often it does the opposite. At the same time, there have been many examples of generosity of spirit, kindness and compassion and creative endeavour which come from a healthier place. For some, the enforced situation is bringing positive experiences of connection and slowing down. Families and work colleagues have found different ways to stay connected and look out for each other. Some people might experience the trauma response of freeze and fragment in the ‘here and now’, particularly those who are critically ill. For most of us though, it is likely to bring re-traumatisation. The level of this will vary, depending on our current circumstance and our history. Our response is due to the level of actual risk to life (as perceived by our neuro-physiology) in the present plus that which is triggered from the ‘there and then’. I have been thinking about the healthy self, how important it is that we are able to invoke that part within ourselves and how challenging that can be in stress-inducing circumstances. I was asked at one of the Masterclasses to say more about the healthy self, and I realised that I had been talking about it as an intellectual idea rather than an embodied sense of, and connection with, ourselves. When we are in our ‘healthy self’ we have reduced our stress and anxiety levels, and through so doing we can find a place of safety within. Many of us have anxiety levels set at a high ‘normal’ rather than one which is congruent with feeling safe. The healthy self is a place of grounded connection with our inner experience, where the data from our body can be accessed and processed by our frontal lobes, and where the responses of the ‘reptilian brain’ of fight, flight or freeze are not needed. Of course, these responses are vital when we are in actual, immediate danger. However, when they are constantly being reactivated by retraumatisation rather than the ‘here and now’ they drive survival behaviour, which is not about living but surviving. They are also damaging to our immune system, so at this particular time are very unhelpful to our protection. This connection with the healthy self , via self-regulation, needs regular practise using techniques or processes which bring us into that state of calm connection with ourself. We are so used to flipping from trauma pain into survival responses that we need to practise being able to connect with a different part of ourselves that can bear and process the pain. When we are in a calm, grounded state we can sue the reflective capacity of the human brain to enquire into our felt experience. Having ‘a practice’ to develop this ability, means using deep breathing techniques, mindfulness, meditation, listening to music, reflective journaling and similar approaches to calming the anxiety and connecting with an internal sense of safety. Any approach we use needs to result in a connection with our body and our internal experience, and to shut down the ongoing chatter in our brain. In our healthy self we can be aware of what we are feeling, for example my sadness this morning, and allow it to exist. We don’t need to push it away or block it out with activity or distraction. We can welcome it and allow it to go when we have acknowledged it. We can feel into our body, and explore which parts feel strong and which parts feel more vulnerable? We can note those without taking action. Some might then make an image that captures this experience or comes to us as we breathe deeply. We can reflectively explore that image to arrive at some understanding of what is going on for us. Some approaches may be more difficult at this time, for example, contemplative walking or spending a lot of time in nature. However, rather than become angry or turn to a ‘victim-attitude’, we can find other approaches or ways to get a similar experience. We are resourceful, we can find ways and practise them regularly during during each day to practise self-regulation and connection with the healthy self. We don’t need to spend a lot of time but enough to build up our ability to reconnect with ourselves in this strange and demanding time. As coaches, if we can do this, we can also be more available to our friends and family. We can be the calm presence in a time of turmoil. Jules Vaughan Smith April 2020 #traumainformedliving  I have become aware of how often I refer to ‘parts’ of our selves when working with coaches in supervision and with clients and how it is always met with ‘that is so helpful’. I thought I would share this approach and my thinking more widely. Examples include: A coach saying, “the client is very lacking in confidence”, reframed as “part of the client is very lacking in confidence”. A client saying, “I feel overwhelmed by this situation” becomes “part of me feels overwhelmed by this situation”. Hearing ourselves say “I feel so despondent” and reframing it as “part of me feels so despondent”. A coach saying, “this client can’t access his feelings” becomes “part of this client can’t access his feelings”. The first statements imply the experience is all encompassing and suggests an identification with the feeling or narrative. Such identifications come from the survival self. It is not true that ‘all of us’ is caught up in this experience, we have access to other resources which can reflect on and engage with the context we are responding to. In trauma the ‘psyche’ splits, creating the survival and traumatised selves. The healthy self continues but access to it has been diminished by the trauma (see previous postings). This figure (© Franz Ruppert), illustrates that split. Due to the fragmentation that occurs with trauma, within each of the survival and trauma selves there are different ‘parts’, different expressions of the survival self and strategies, or the trauma self. Each ‘part’ carries memories, beliefs and feelings which connect to the ‘there and then’. By talking of ‘part of you/me’ we recognise that this part exists, and leaves the possibility open of other parts emerging from the healthy self as resources to be accessed. The healthy parts are more consistent as they are unaffected by the trauma, other than being repressed by the survival self. From that self we know what is healthy for us, can think clearly about what is our business and what is the business of others, and what action is in our best interests. In coaching, we want to encourage the healthy parts to have a voice, to challenge the survival part narrative. Whenever you hear yourself make statements which sound all encompassing, change your language to ‘part of me feels’. Encourage those you supervise or coach to experiment with that as well. It is a simple way of reframing and recognising the splits in the psyche. It is important also to welcome all parts, while we are reframing to ‘part of you feels overwhelmed’ we need to make it clear that that part is welcome, it is not being rejected. This is because many people dislike or want to reject the parts that are present, particularly those from the trauma self, but also those from the survival self. All parts are important in terms of understanding the internal system. We can ask the client to say more about a part, and explore what other parts are also present. A client the other day arrived saying “part of me is fine, the other part of me is wobbly”, my response was both parts are welcome. That allows both to be present. In his book Internal Family Systems Therapy, Richard Schwartz takes this to a further stage by identifying and naming parts as sub-personalities within the internal psyche-system of the individual. He talks of trauma causing the self-system to break down, with parts of the self becoming polarised and at war with each other. I read this as being similar to Franz Ruppert’s approach with the splits in the psyche and the fragmented selves. Schwartz identifies three categories - Exiles, Managers and Firefighters. Within Ruppert’s model, Exiles are trauma parts, with Managers and Firefighters being survival parts. Schwartz also talks of the undamaged essence-self, in Ruppert’s terms the healthy self, that is confident and can emerge to lead the healing process. He refers to this as self-leadership. The parts that emerge, he states, may not be aware of other parts of the system, hence the naming of them and allowing for other parts to emerge. While he is writing for therapists, if coaches are interested, there is much that can be transferred appropriately and usefully within coaching practice. Julia Vaughan Smith September 2019 (Translated by Coleman Banks)

If you have read the last blog, you will have read about the idea of parts of ourselves and how useful it can be to refer to a feeling or thoughts, as ‘part of me feels’. If you haven’t read it yet, I suggest you do before you read on. This poem can be read as the Self welcoming all our parts with gratitude and compassion: This being human is a guest house. Every morning a new arrival. A joy, a depression, a meanness, Some momentary awareness comes As an unexpected visitor. Welcome and entertain them all! Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows, Who violently sweep your house Empty of its furniture, Still, treat each guest honourably. He* may be clearing you out For some new delight. The dark thought, the shame, the malice, Meet them at the door laughing, And invite them in. Be grateful for whoever comes, Because each has been sent As a guide from beyond. *or she… I have put this in a blog so the information can always be found. I am often asked about further reading so here is my list which I hope will take you in an interesting direction personally and professionally. I haven't included all my recommendations, you might make out a few additional ones in the photo, or go to the extensive bibliography in my book 'Coaching and Trauma'. You can also always contact me if you need help about where to start or in relation to a particular interest. I love books and reading so I cover a range of topics in my inquiries. Professor Franz Ruppert www.franz-ruppert.de His website has some papers and presentations in English "Who am I in a traumatised society?" (2019) Green Balloon Publishing "My Body My Trauma My I" (2018) Green Balloon Publishing (written with Harald Banzhaf) "Early Trauma" (2016) Green Balloon Publishing " Symbiosis and Autonomy" (2012) Green Balloon Publishing "Trauma, Fear and Love "(2014) Green Balloon Publishing Vivian Broughton www.vivianbroughton.com Vivian is a leading practitioner of Franz’s work in the UK. Her website has many blogs and papers of interest. Her book ‘becoming your true self’ (2014) is written for a lay readership and published by Green Balloon Books. An updated version was published in 2016. Bessel van der Kolke "The Body Keeps the Score. Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. 2014." Allen Lane Sue Gerhardt "Why Love Matters" (2004) Brunner-Routledge Gabor Mate "In the Realm of the Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction" (2008) Vintage Canada "When The Body Says No" (2003) Wiley Donald Kalsched (a Jungian) "The inner world of trauma" (1996). Brunner and Routledge "Trauma and the Soul" (2013). Routledge Peter A Levine "Walking the Tiger Healing Trauma" (1997) North Atlantic Books "In an Unspoken Voice" (2010) North Atlantic Books Babette Rothschild "The Body Remembers" (2000) Norton Daniella F. Sieff "Understanding and Healing Emotional Trauma" (2015) Routledge Irvin Yalom "The Gift of Therapy" (2001) Paitkus. I think this is a must read for any coach, therapist or counsellor. I have recently read a remarkable book, The Apology, by Eve Ensor. in this short book she writes the apology she would have liked her father to make to her for the years of sexual and emotional abuse he subjected her to. When I saw her being interviewed she said she had written this as she was aware that all of her life she carried a longing for such an apology and this was a negative undercurrent to her living fully. When it was completed, she said that longing had gone. Within Identity orientated Psyche-trauma theory, such a longing is a sign of a continuing entanglement with the perpetrator. Resentment, hate, compliance and rebellion are also signs of being caught in the victim:perpetrator survival dynamics. In her book, Ensor explores her father's history, and the sources of his own trauma in childhood. Traumatising relationships are multi-generational, the trauma is passed down through the bonding, or lack of bonding, and parenting process unless personal work is done. She also writes in detail about what he subjected her to, and imagines his thoughts and feelings about those actions and about her. Towards the end of the book he takes responsibility for his action and the pain that he caused her. It is unusual for perpetrators to take responsibility for their behaviour and the impact of that on the victim. Too often they seek to justify and absolve themselves. The deep shame experienced means that they try to cover up their actions and often continue to intimidate and threaten victims into silence. They have much to lose in terms of reputation. However, in so doing they remain locked in their own trauma of being a perpetrator. Professor Franz Ruppert talks of trauma of identity (not being wanted), trauma of love (not feeling loved), trauma of sexuality (sexual abuse), and trauma of perpetration within the perpetrator. This book gives us some insight into how to break these entanglements. Firstly to connect with ones own pain and trauma, with compassion, telling the truth of what happened and by whom. We need to go into our own experience and not look to the other for apology or as a focus for our rebellion or hatred. Once we can do this, and let go of the survival responses, we are better able to see the perpetrator as a traumatised person. We can see that it wasn't about us, it was about them and their history. We can allow compassion to arise for what they endured and keep in contact with our own pain. If we only engage with compassion for them, and deny our own, we are entangled. We must face up to our own emotional reality, and let go of denial and illusion. As perpetrators, we too need to look into ourselves with compassion, connecting with our own pain and trauma. Having done that, we are better able to take responsibility for our actions and the pain we have caused. We can being compassion for those we have hurt. I am using 'we' as while we might not have sexually or emotionally abused another, we may well have caused pain to ourselves or others through our survival strategies. Until we take responsibility, for what we are rightly responsible for, we remain entangled with those we hurt. In doing so, we need to be careful to focus on our actions, and not to take responsibility, as victims sometimes do, for the behaviour of perpetrators. Perpetrators, who wish to, need support to work through these processes. It seems that Ensor's book has helped many to become fully aware the consequences of their actions, and find ways of releasing themselves from that part of their trauma biography. Breaking entanglements isn't about forgiveness in the sense of ‘I forgive him/her, and must accept my pain as s/he couldn’t help it’. This is still in a victim survival attitude. In some therapies in the past I have witnessed abused ‘client’s’ being encouraged to bow down before their abusive father and thank him for their life. This is not healthy. This is about denying our own emotional reality to retain an illusion of love. It is true our parents gave us life, as their parents gave it to them, and so on back into our ancestors. However, in some cases they also carried and passed on great pain and suffering. Whether writing the apology for ourselves in this way frees all of us from any entanglements we carry, I am not sure. But Ensor has presented a powerful approach which may bring strength or courage to many. Gabor Maté, in a recent talk on Healing as a Subversive Act identified the major health indicators in our society are rapidly growing. In those indicators he includes autoimmune diseases, mental health, and addictions. The number of prescription medicines taken also increasing at an alarming rate. In coaching we meet those with depression, anxiety, other mental health symptoms, work addictions and who can feel trapped by their work and life decisions. Maté talks of healing being a highly subversive act in our culture as it is about challenging the idea that someone’s value is dependent on how well they fit into the unhealthy culture which surrounds then. This resonates with me powerfully, in terms of coaching people in unhealthy organisations or roles that are causing them suffering who are offered coaching to enable them to ‘fit in’. That has never been my idea of a worthwhile activity. Nor is it my job to give a client my opinion, or direct them towards my view of their life, but I can offer them an idea that life doesn’t have to be like that, and that they could explore what might bring more joy, meaning and give them a life worth living.

What is it to live a life worth living? To have energy and to feel alive? Is this part of the coaching contract? Some coaching only focuses on improving performance and doesn’t attend to clients’ lives. That has never been my approach. Having a holistic approach means attending to clients’ wellbeing in all areas of their lives. Some areas they might not wish to explore in coaching, but we can hold the idea of the totality of their lives in our work. What is it to change our lives? What are we changing? Changing so we don’t change back requires attention to the inner dynamics created by how became who we are, the sense we have of ourselves, what our defence systems are and why they are needed, the influences are of the ‘there and then’ of early experience on the ‘here and now’ of the present, and what our felt experience is. Some clients feel stuck in changes they want to make, or have developed ways of engaging with work, others and themselves which is unhealthy for them. They want to change but seem unable to access the inner resources needed to help them. If we want to support our clients, and ourselves, in living more fully and having more satisfying relationships with others and with work, we need to understand the internal dynamics that prevent this so that we can help clients change these processes if they want to. The major factors are our early experience of feeling wanted, loved for who we are and protected by those we should be able to trust. You will have noticed that I have not yet used the word trauma in this piece. However, this is the core of not being wanted, loved or protected. The lasting effect of early experience prevents us being able to create a meaningful and fulfilling life for ourselves and results in high levels of stress and anxiety, which we take for normal. This is open to change; by understanding how the ‘there and then’ is acting in our life, we can separate ourselves from the past influences and claim a healthier life for ourselves. As a result, we can find the internal resources that can help bring about change within ourselves, and thus in our work and relationships. If we don’t, we will continue to use the resources of survival to direct our lives and fail to thrive as autonomous beings. The Masterclass ‘Coaching to Change Lives’ on November 28th 2019 (www.coachingandtrauma.com), introduces the dynamics which stop and liberate us to live healthier lives in all ways. We draw on the work of Professor Franz Ruppert which provides a simple way of understanding the highly complex issue of trauma. June 2019 How does early experience stay in our neuro-physiology? “Trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on mind, body and brain.” Bessel van der Kolk Our unhappiness, confusion, relational difficulties, career problems, chronic illness or stress, fatigue and/or inability to create a healthy life for ourselves all have roots in our early developmental experience. For many this can be hard to accept, as the trauma survival strategies of denial, illusion and distraction stop us from engaging with our reality.

Trauma is a lasting imprint on our neuro-emotional-physiological systems. By the term physiology I refer to all our body systems, the immune, endocrine, skeletal, circulatory, digestive, respiratory and other essential components of staying alive. Bessel van der Kolk (The body keeps the score) states that ‘the body bears the full force of the trauma’. This internalised imprint, our trauma, is our response to life threatening events from conception onwards. We experience such events through our senses and the parts of our brain that are attuned to responding to danger, to processing and storing our experience. In the types of experience that result in trauma, the child is unable to make use of her flight or flight responses, either because the danger is overwhelming or because the responses are too weak (as in a young infant). When that happens a different neuro-physiological process takes over. This results in dissociation from the experience, ‘playing dead’, numbness, and in stress responses which are toxic to the infant or child. Such responses leave a lasting imprint on the body systems. This imprint, or memory of experience, is held in the networked pathways of our neuro-emotional-physiological systems, at cellular level. This memory is the molecular, biochemical and physiological alterations to the cellular development. The systems continue to develop but in an altered state as a result of the intense experience. This includes the developing brain and how the different parts of the brain are able to communicate with each other. For example, the ability to evaluate the danger in the here and now is affected as part of the trauma and results in the neuro-emotional-physiological systems being activated as they were at the time the trauma pathways were laid down. As the brain develops in the first years of life, the relationships around us leave a lasting impact on the sense of ourselves, how wanted and lovable we feel for ourselves, and how safe and protected we feel with others. We are relational beings and the nature of early relationships shape our developing brain having a lasting impact on how we see ourselves and how we are able to relate to ourselves and others. Much is now being written about the neuro-emotional-physiological impact of experience and how it continues to affect us throughout our life unless we do appropriate personal development work to change those established pathways and prevent the restimulation of toxic levels of stress. The continuation not only leads to unhealthy relationships with ourselves and others, including our children, but to chronic physical ill health and to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. These old pathways, which have been activated over and over throughout our lives, as unconscious responses, can be changed. New pathways can be established which means that we can step out of our trauma responses. This takes personal commitment and doesn’t happen immediately; however, gradually internal change is possible through body based work which ‘uploads’ new neuro-physiological-emotional information at cellular level. Coaching can contribute to this through enhancing trauma awareness and understanding, by bringing into conscious awareness behaviour and emotional responses to the ‘here and now’ which may have their roots in the ‘there and then’, by teaching self-regulation exercises and by ensuring that, as coaches, we are not entangling our clients through our trauma responses. Julia Vaughan Smith April 2019 Ruppert. F. (Ed) (2018) My body, My trauma, my I. Green Balloon Publishing UK Gerhardt. S. (2004) Why love matters. How affection shapes a baby’s brain. Brunner-Routledge. van Der Kolk. B. (2015 ) The Body Keeps The Score. The Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma. Allen Lane Levine. P.A (2015) Trauma and Memory:Brain and Body in a search for the living past. North Atlantic Books Maté. G. (2013) In the realm of the Hungry Ghosts - close encounters with addiction. Vintage Canada Maté. G. ( 2003) The Body Says No. Wiley Rothschild. B. (2000) The Body Remembers: The psychology of trauma and trauma treatment. W.W. Norton & Company Having run workshops and masterclasses and spoken at conferences I have become aware of 5 different ways in which people engage with trauma from a practitioner perspective.