|

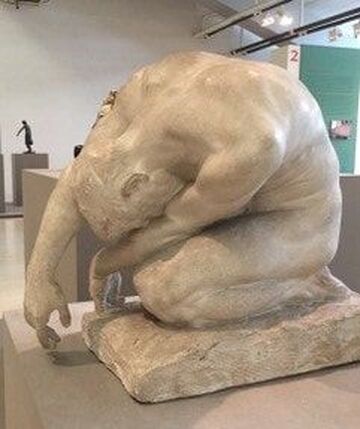

Suicide has been in the news recently, with the deaths of two high profile people and a series of deaths at the University of Bristol. Those who lose someone close through suicide often ask “why?”; “why now?”; “ “what signs were missed?”. Some feel guilty or angry, and all feel the empathetic pain of someone dying alone in such a way.  While some who commit suicide may have mental health diagnoses, many don’t. Few of us have not been touched by suicide by a family member or within our social or community circles; while writing this I have counted 6 suicides in my circles. The data from the Samaritans[1] tells us there were 6188 suicides in the UK in 2015; the group with the greatest suicide rate is men aged 40 – 44; the rate by men being three times greater than for women. A recent publication analysing suicides in doctors under investigation found that medical practitioners carry a high suicide risk. The number of suicides annually is significant, affecting many people. So why are two celebrity suicides given so much publicity and what does it have to do with coaching? There is a myth that success in terms of achievement and making money protects people from the inner pain of trauma associated with an intense sense of aloneness, emptiness, abandonment, lack of close attachments, and feeling unsafe. However hard we work to be successful professionally will not override our early history and our emotional vulnerability to these feelings. It is an illusion that is held by many and when we see the news, this illusion is challenged. It is rare but can happen that our clients imply they ‘have had enough’ or ‘it is better if they just leave the world’; often this might be said as a throw-away line so that we are not always sure we have heard what we think has been said. It is not true that those who talk of it never do it, that it is ‘just a cry for help’. Suicide can bring great judgements from others and can be felt as a passive-aggressive attack on those who care for the person. But to refer to someone’s suffering as ‘just a cry for help’ is to miss the point. Anyone implying that they are thinking of ‘ending it all’ is in emotional pain. Through his clinical work, Professor Franz Ruppert has developed a simple way to understand the deeply complex matter of psychological trauma. This is the lasting impact on our psyche and body systems from early attachment dysfunctions and levels of unbearable stress; from conception onwards. When we have grown up without the feeling of being safe, or of being helped to regulate our unbearable stress and distress, or been subject to abusive relationships, or been emotionally abandoned, we are left with scars that we bury deeply within us. Ruppert’s model (left) describes the trauma as being the lasting splits in the psyche. To survive traumatising experience emotionally, the trauma feelings are deeply buried (within the trauma ‘self’) and instead a ‘survival self’ emerges to ‘press on regardless’; to override the pain and to cover up the psychological wound (which doesn’t heal). While a healthy self remains, the extent to which its resources can be accessed depends on the level of trauma experienced. The survival self uses various strategies, one of which is illusion “If I work hard I will be safe” or “If I work hard I will be loved” or “If I have lots of money I will be safe” or “if I climb this ladder high enough I will be okay” (only to find, after all the hardship, ‘the ladder has been up against the wrong wall’ - Joseph Campbell). Another survival strategy is addiction to work, alcohol, drugs, sex, shopping. Like all addictions the initial hit feels good, but then it feels much worse, until the next hit. The trauma may become somatised, that is expressed in the body through intense pain or auto-immune disease; from which addictions to pain killers may result. According to Ruppert[2], suicide is a survival strategy. It is the attempt, by the survival self, to ‘kill off’ the internal pain and distress that is associated with the trauma self – the intense loneliness, abandonment, lack of safety, terror and rage. These are the feelings of a child from a traumatising situation. It is the ‘end of the road’ for trying to manage that pain by any other means whether professionally successful or not. The idea can bring a sense of relief that the battle could be over. Some who consider suicide, and may act on it, may feel they are a burden on others and it would be better if they just left the world. This is the survival self’s response to the pain of the very young child who wasn’t wanted or whose parents were unable to welcome the child as he or she is. If clients make such comments about ‘opting out of life’, take it seriously and check if you are hearing them correctly. Tell them you take it seriously and can only imagine (if you can) what emotional pain they must be for that to seem like a solution. As coaches, our function is then to facilitate a conversation about who else the clients have told (this helps us know if a partner or GP knows), and what help they are getting. Our aim should be to encourage them, being directive if we need to, to talk to a partner and tell the GP. We cannot make clients do either, but we can offer our support to their thinking through how they might do that. One of our clients might commit suicide as if ‘from nowhere’. This is a shock and common responses are to feel we should have seen the signs. However, often the signs are so deeply hidden that they are not there for others to see. People develop very effective masks. If clients talk of or commit suicide, we need to get our own professional support through supervision. While it is rare for a client during coaching to talk of or commit suicide, it is helpful to understand what psyche-trauma really is, and how it presents in adults. From that theoretical understanding we can then evolve coaching responses that are appropriate and be clear about the boundaries between coaching and therapy in working with trauma. In our Masterclass on 26th July, ‘Coaching to Change Lives’, Jenny Rogers and I will talk about this way of understanding trauma and what it means for transformational coaching. For information and booking www.coachingandtrauma.com. Julia Vaughan Smith 17th June 2018 [1] https://www.samaritans.org/sites/default/files/kcfinder/files/Suicide_statistics_report_2017_Final.pdf [2] Professor Franz Ruppert, Professor of Psychology, University of Applied Sciences, Munich, Germany. www.franz-ruppert.de

0 Comments

|

Julia's BlogArchives

May 2023

Categories

All

Access Octomono Masonry Settings

|

Becoming Ourselves | Julia Vaughan Smith

© Julia Vaughan Smith 2017-2023 All rights reserved | Privacy Practices | Coaching & Trauma website

Website design by Bright Blue C Design Studio | Photo credits

Website design by Bright Blue C Design Studio | Photo credits

RSS Feed

RSS Feed